Beyond life. Something like a runner’s high.

Kawamata explains that he has enjoyed carpentry work much more than painting since his teenage years, although ironically, he enrolled in oil painting at Tokyo University of the Arts. Since around 1980, his production has taken on the characteristics of projects.

“I give form to things that I personally find interesting in the ordinary life that I lead, figuring that if it should transcend that, it will turn into an artwork. It’s something like a runner’s high. I feel that the adrenaline will kick in so long as I’m running, and I’ll be able to get somewhere beyond my own ideas.”

There are five key words relevant to Kawamata’s projects.

Keywords related to Kawamata’s production

Site

Materials

Process

Approach

Action

Like a circus tent, put up, then moved again.

Apartment project Tetra House N3 W26 Sapporo, 1983

“When I did the project at the private house in Sapporo (Photo 1), one of the participating students had parents who owned a lumber shop. We were able to borrow old lumber from the shop and build the piece. Working together over the course of two weeks, we repeatedly put it up, then pulled it down again. I’ve kept the same working method since this Sapporo project, although factors like the time, place, and people do change. It’s a bit like a circus tent—putting it up, taking it down, and moving again. The planks of wood looked as if they might come crashing down at any time, so the work was often described as “dangerous.” Production was being carried out without any indication of its completion, so it caused friction with the locals, as you would expect. People were wondering what it was all about. I even received demolition orders. People were divided about my work back then—half of them in denial and half participating and cooperating, and this definitely made things tough for me as the artist. While it was not my intention to be controversial, my work was gradually taking on a life of its own. At the time, it was even referred to as “visual terrorism.”

On the other hand, while working on site, I found myself fascinated with the process itself.

I felt that, for me, it was the experiences one has while producing the work that actually constitute the work. I don’t think about anything until I go to the site. Only after I get there do I start to think about what’s possible as I toss around ideas with different people. In any one project, a lot of things are going on, and that’s what makes them interesting. I felt it was both activity and actuality.”

This is what would later become the “work in progress” that is Kawamata’s area of exploration and that appears in the titles of his works. “work in progress” carries the senses of “in preparation,” “in progress,” and “under construction.” This temporary, unfinished quality later came to be seen as a defining characteristic of Kawamata’s projects.

Lumps or parasites? Like sticking chewing gum under a table.

“This is a project I started in 2006, attaching small hut-like structures to things here and there. In Madison Square Park in New York, I assembled 13 huts and installed them up on trees for about half a year. They were imaginary houses; houses that look as if people live in them but that you cannot actually visit. And these houses suddenly appear one day. I felt as if they were truly something like lumps or parasites, something like that.

When I did the work at the Paris Mint, I tried to create something that would be hopefully difficult to discover, with some strange, anonymous thing stuck on it. I enjoy that kind of thing. I also stuck these things to the Centre Pompidou and the Napoleon monument in Place Vendome (Photo 2) in Paris, and in Florence, to the Centro di Cultura Contemporaneo Strozzina, which was built during the Renaissance. People often stick their chewing gum under a table, right? This work was an act like that. In the West, my work is sometimes called graffiti. It’s sometimes judged like that. I’m not talking about the alienation effect, but what I’m trying to do is to take some kind of action.”

Tree hut in the Place Vendome, Paris, 2013

I’ve become interested in the purity of fermentation in a bubble.

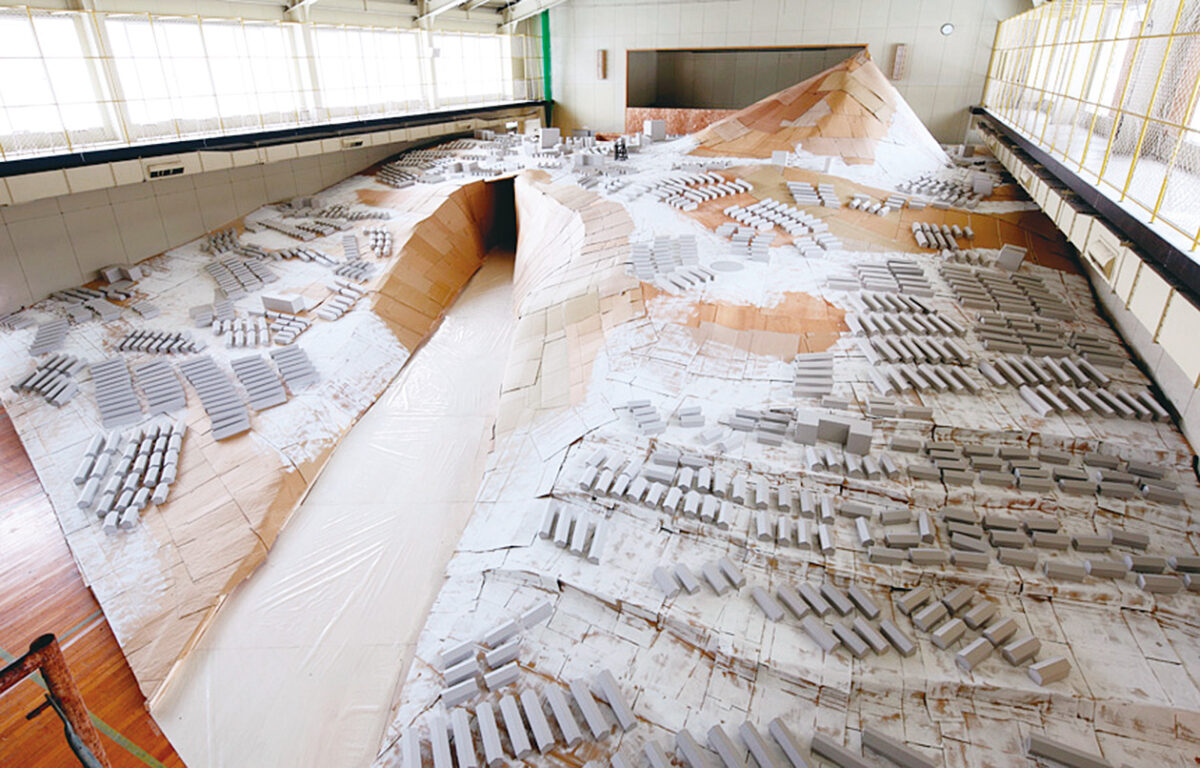

“A recent project is Hokkaido In Progress (Photo 3), which started in 2010. We rented an elementary school that was no longer in use, and the project members were all local people like classmates from the local elementary, junior high, or high school. We received no funding, and we worked by collecting membership fees. In other words, it was a “closed” art project. We’ve been working on it for four years. We come up with plans for our ideas through discussions and making decisions all together, then develop the work the following year. In the art events that you see all over the place these days, the artist is presented as a “good guy,” and it’s all about enjoying art and having fun. And in the past, I was doing the same kind of thing, for sure, but I feel that it’s OK for the creator of the work to decide who’s going to see it. This is a project where only project members can view the work.

We take part in international exhibitions, triennials, biennales, and so on, but we do what we want to do for ourselves. I think that self-centered projects are OK too. In 2005, I was the artistic director of the Yokohama Triennale, and even then, I was wondering who was going to come and view the works. I’ve been thinking about this issue ever since then and have come to the conclusion that a project can be closed. I’ve become interested in the purity of the fermentation that happens when you’re in a bubble. Rather than having lots of different people see the work and “spreading it out,” I’d prefer to return to the bubble.”

We do hope that people will look forward to seeing how Kawamata’s long-term project in Sendai evolves.

Hokkaido in Progress Mikasa Project, Daytime Landscape of a Coal Mining Town with the Snow Melting, Installation view, 2014